ISBA Development Site

This website is for ISBA staff use only. All visitors should return to the main ISBA website.

This website is for ISBA staff use only. All visitors should return to the main ISBA website.

Jody Raphael was in law school in 1968 when Martin Luther King and Robert F. Kennedy were assassinated within months of one another.

Jody Raphael was in law school in 1968 when Martin Luther King and Robert F. Kennedy were assassinated within months of one another.

“I wanted to be a criminal defense attorney, but 1968 seared into my soul,” Raphael recalls. “By the end of the summer of 1968, I really had, without quite knowing it, made a decision that I was going to try to use what skills I had to make a difference and to do what I can about the issue of violence in America.”

Indeed she has. Raphael, a senior research fellow at the Schiller, DuCanto & Fleck Family Law Center at DePaul University College of Law, has become an international expert in violence against women and girls and is one of the leading advocates for the victims of domestic sex trafficking.

Raphael was one of four distinguished Illinois attorneys who shared their stories as part of the ISBA’s Midyear Meeting program, “Lincoln’s Legacy: Lawyers Protecting Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness.” She was joined on the panel by retired U.S. District Judge George Leighton, one of the state’s leading civil rights attorneys before he took the bench; Terrence Hegarty, a former president of the ISBA and a vocal opponent of the death penalty; and Camilla Taylor, a dedicated advocate for the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgendered community.

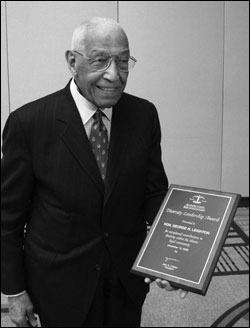

ISBA President John O’Brien told the audience that the program, which was the closing event in the ISBA’s Lincoln Bicentennial celebration, was designed to show how today’s lawyers are following in Lincoln’s footsteps on the front lines of social justice. In addition to the panel discussion, the program featured a keynote address by Illinois Attorney General Lisa Madigan and the presentation of the ISBA’s Diversity Leadership Award to Leighton.

ISBA President John O’Brien told the audience that the program, which was the closing event in the ISBA’s Lincoln Bicentennial celebration, was designed to show how today’s lawyers are following in Lincoln’s footsteps on the front lines of social justice. In addition to the panel discussion, the program featured a keynote address by Illinois Attorney General Lisa Madigan and the presentation of the ISBA’s Diversity Leadership Award to Leighton.

“President Lincoln was a famous Illinois lawyer who made a difference,” O’Brien said. “At a crucial moment in our nation’s history, he stood up for the rights of black Americans to be free. . . . Today, we have another famous Illinois lawyer, Barack Obama, who has already made a difference in so many peoples’ lives as an organizer on the south side of Chicago and as a civil rights attorney. And he has made a ‘Call to Service’ a cornerstone of his presidency.”

The panel discussion, moderated by Phil Ponce, host of WTTW-TV’s Chicago Tonight news program, highlighted the civil rights issues that Raphael, Leighton, Hegarty, and Taylor were called to serve and what inspired them to pursue those callings.

Raphael said her research has demonstrated how young girls are recruited into the sex trade because of poverty and held there by violence and coercion. She personalized the lives of the victims by telling their stories in their own words—or in the words of their oppressors. She quoted one ex-pimp as saying: “I helped girls no one else would. I always picked up throwaways and runaways, dressed them up and taught them how to survive. I looked for girls who needed things, who would do whatever they needed to do to escape from their messed-up homes and their messed-up parents.”

Similar to Raphael, Taylor said she found her calling in law school. “I was inspired by reading cases that revealed the transformative effect that courts can have, that individuals can have by going to court and by demanding what’s right,” she said. “For me, it was a search for the most fulfilling way to use my legal education.”

Taylor’s search led her to Lambda Legal, the oldest and largest national organization advocating for the civil rights of the LGBT community. As senior staff attorney for the organization, she has litigated a number of high-profile cases, including a landmark case in which the Iowa Supreme Court recognized the rights of same-sex couples to marry.

Taylor said Iowa was identified as a favorable location for the marriage equality lawsuit because of its humanity, common sense, and dignity, as well as a “remarkable history of doing the right thing—often very early and long before other states.”

“We stand on the shoulders of giants,” she said. “The precedents we relied upon that are so meaningful to us are precedents that were developed by civil rights lawyers who advocated for racial equality, for equality for women, advocated on behalf of children who were born to unwed parents . . . [and] advocated on behalf of immigrants. So we have a legacy that has been so crucial to our success and we are deeply indebted to the civil rights leaders who came before us.”

Hegarty was motivated to become a lawyer by a strong sense of social justice at an early age. As a teenager, Hegarty could not understand why police officers would harass him for merely standing on a street corner. After he became an attorney, a substantial portion of his practice focused on lawsuits against the police for violence. More recently, he was recruited to advocate against the death penalty.

“I’ve never understood why we continue with the execution of people,” said Hegarty, of the Hegarty and Hegarty law firm. “When the Innocence Project came and journalists proved that innocent men were executed or about to be executed, and then the Illinois Coalition against the Death Penalty asked me to be involved, it occurred to me that [abolition of the death penalty] could happen. I joined just because I couldn’t see how you couldn’t join.”

Hegarty called the death penalty a “brutal, senseless act of state violence” and “an anachronism we must end.” In addition to its record of executing innocent men, he said, the death penalty is racist. “When the victim is white and the defendant is black, we almost always have the death penalty; the reverse is not true,” he said. “It is arbitrary, it is unfair, and it is extremely expensive. There has been talk of one case outside of Illinois costing $10 million. In our case, $3 million has occurred.”

Hegarty told lawyers in the audience that it is their turn to make a difference. “This thing is all but dead,” he said. “But it cannot end without attorneys’ support. It is our call to end it.”

Judge Leighton, who celebrated his 97th birthday in October 2009, confessed that his aspirations for becoming a lawyer emanated from much more humble roots—the ones that wrapped around his legs in a cranberry bog.

“I was about 12 years old,” he said. “It dawned on me I wanted to be a lawyer. I had never spoken to an attorney. I hadn’t known one. What could have done this? . . . It must have occurred to me as I was sitting there with my knees getting eaten up and the sun beating down that there just had to be a better way of earning a living.”

As an Illinois trial attorney during the 1950s and 1960s, Judge Leighton handled a number of high-profile constitutional rights cases, including a few that reached the U.S. Supreme Court. He said that one of the cases that best exemplified “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness” was one in which he successfully challenged Alabama’s Boswell Amendment. A three-judge court found that the amendment, which required citizens to be able to explain a provision of the U.S. Constitution to be certified as an elector, had been enacted for the specific purpose of disenfranchising blacks.

Judge Leighton, who now serves of-counsel to the Neal and Leroy law firm in Chicago, said he had seen great strides in civil rights since he started his practice in Chicago at a time when “a black man couldn’t drive a cab in the Loop.” He prefaced his remarks with a tribute to President Lincoln for bringing an end to slavery.

“I wouldn’t want it left unsaid that the man who brought us here this afternoon was a profound and great human being,” he said. “If you spent hours reading all of the biographies of all of the presidents of the United States, you won’t find a single one who by signing one document gave liberty to millions, as Lincoln did when he signed the Emancipation Proclamation.”

Ponce concluded the discussion by asking the panelists about the obstacles they faced in their work.

Raphael pointed to the “media obsession” with international trafficking of women. “Although there has been a lot of media concern about girls and women who are trafficked internationally into Chicago, the bulk of the girls and women involved in the Chicago sex trade industry are Chicago women,” she said.

Hegarty and Taylor said their biggest obstacles have been people who believe it’s “too soon” to push for reform. Taylor said such doubts have been expressed by their own supporters—people “who believe in their hearts that it is inevitable that we will win, but who believe that it is too early or we may be sacrificing other causes that are dear to us by asking for too much too soon and that maybe we should wait for a better time when it is more convenient.”

So, her biggest challenge is “having to persuade people that it’s always the right time to demand equality, that it’s never appropriate to postpone such demands.” ■