ISBA Development Site

This website is for ISBA staff use only. All visitors should return to the main ISBA website.

This website is for ISBA staff use only. All visitors should return to the main ISBA website.

September 2015 • Volume 103 • Number 9 • Page 32

Thank you for viewing this Illinois Bar Journal article. Please join the ISBA to access all of our IBJ articles and archives.

The Illinois spousal maintenance guidelines were enacted to provide clarity and uniformity in maintenance calculations. But they raise their own set of questions. This article summarizes key provisions and highlights issues that might arise as cases progress from the trial to appellate courts.

At first blush, it might seem the recently enacted spousal maintenance guidelines in the Illinois Marriage and Dissolution of Marriage Act ("IMDMA") would reduce family lawyers to mere scribes solving an eighth-grade algebra problem. The amendments add the title phrase "Entitlement to maintenance," suggesting that maintenance has now become a right and not a demonstrated need. And, they prescribe mathematical guidelines to set its amount and duration.1

But it soon becomes evident that skillful advocacy is still required under the new formula, perhaps more than ever. This article summarizes key provisions of the amendments and highlights issues that might arise as cases progress from the trial to appellate courts. The amendments discussed herein include both Public Act 98-0961 (effective January 1, 2015) ("maintenance guideline amendments"), and Public Act 99-0090 (effective January 1, 2016) ("IMDMA rewrite").

Impact on child support

First, let's clear up a misnomer. The so-called maintenance guidelines are actually amendments to both maintenance and child support.2 There is a direct interplay between maintenance and the calculation of net income for child support.

A new subsection to section 505(a) adds a deduction for "[o]bligations pursuant to a court order for maintenance in the pending proceeding actually paid or payable under Section 504 to the same party to whom child support is to be payable."3 This means that the amount of maintenance will be deducted from the payor's net income for purposes of calculating child support paid to the same recipient.

Consequently, maintenance must be determined before child support. The practical effect on pretax cash flow is that as maintenance increases, child support decreases - often dramatically. Since maintenance (unlike support) is typically taxable/deductible for income taxes, it is important to calculate the after-tax cash flow to truly understand the financial implications for your client. Unless the parties otherwise agree, a new provision prohibits a court from awarding unallocated maintenance and child support in a dissolution judgment or in any postjudgment order.4 But the court may in its discretion order unallocated support in any pre-dissolution temporary order.

The threshold requirements for maintenance

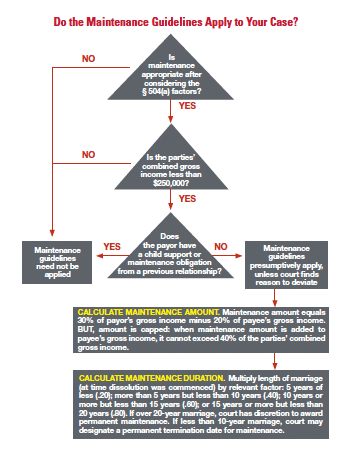

A common misconception is that the maintenance guidelines apply to every divorce case. Actually, the court must first determine whether a maintenance award is appropriate after considering the relevant factors under section 504(a).5 So the lawyer's work is the same as it always has been: preparing and presenting a compelling case in support of or against maintenance. The new twist is that if maintenance is appropriate and if the guidelines are triggered, the argument becomes one over whether to deviate from the guidelines.6

The factors under §504(a) have gotten a facelift under the IMDMA rewrite. Now, for example, the present and future earning capacity of both parties is prefaced with the word "realistic," and any impairment to the realistic earning capacity is considered both as to the recipient and the payor.7 The court must still consider the income and property of each party, but now also "all financial obligations imposed on the parties as a result of the dissolution of marriage."8 The age factor is expanded to include the "age, health, station, occupation, amount and sources of income, vocational skills, employability, estate, liabilities, and the needs of each of the parties."9 There is also a completely new factor of "all sources of public and private income including, without limitation, disability and retirement income."10

If maintenance is deemed appropriate, then the next step is to determine if the guidelines apply. The threshold factors are that the combined gross income of the parties is less than $250,000 and no multiple family situation (e.g., previous marriage with children) exists.11

If that's the case, then the amount and duration of maintenance is calculated according to the guidelines unless the court finds reason to deviate from them. If either threshold element is not met, the guidelines need not be followed. Note that the guidelines are not mandatory for a temporary order, only after the date of the dissolution.

The guidelines as a floor on maintenance awards

The legislative history shows that the guidelines were intended to address "inconsistent awards" throughout the state and provide "uniformity in the law."12 Much of the legislative debate focused on the judge's discretion to deviate from the guidelines, and only one representative raised the concern that they would effectively create a floor on maintenance, in the same way the child support guidelines have become the standard "it."

Arguably, the guidelines are much more than a suggested starting point or permissive option. The use of the word "shall" suggests they are mandatory, or at least presumptive, in the same way the child support guidelines create a rebuttable presumption unless there is a compelling reason to deviate.13

Most family lawyers have experienced the difficult task of trying to convince a judge to deviate from the minimum child support guidelines absent extraordinary circumstances. Whether trial judges will apply the maintenance guidelines just as steadfastly remains to be seen, but the language and framework of both statutes are so similar they might be justified, even obligated, to do so. It is also plausible that even when the triggering threshold is not met, the court could consider the guidelines as a relevant factor in determining maintenance.

The threshold calculations: gross income and "multiple family situation"

The first guideline threshold is whether the combined gross income of the parties is less than $250,000.14 Gross income is defined as all income from all sources, within the scope of that phrase in section 505 of the IMDMA (i.e., the child support provisions).15

Here, for better or for worse, the law of child support and maintenance overlap. Recall that courts have interpreted income very broadly for purposes of child support. The many potential sources of income may quickly complicate the determination of gross income for maintenance, as may uncertainty about the amount of income, the payment schedule, and other issues.

When income is derived from a marital asset also being divided in the divorce, cries of "double dipping" are likely to arise. The public policy in favor of including all sources of income for child support differs - i.e., is more demanding - than the policy behind awarding spousal maintenance, but the amendments don't seem to make that distinction.

Furthermore, the $250,000 income threshold arguably applies the guidelines arbitrarily to some but not all divorcing spouses. Also, the statute is silent about what time period to consider when calculating whether the combined gross income of the parties is less than $250,000. Is it at the time of filing for dissolution? The tax year prior to the filing? Some kind of average during the marriage? The time of trial?

The second threshold had originally been that "no multiple family situation exists," without defining "multiple family situation." The IMDMA rewrite removed this ambiguity. The provision now reads that "the payor has no obligation to pay child support or maintenance or both from a prior relationship."16

In other words, the first family first rule applies. For child support, there is already a net income deduction under section 505(a)(3)(g) for prior child support or maintenance actually paid pursuant to a court order.17 So, if there is a child support or maintenance order from a prior relationship, the guidelines do not apply.

Solving for X (dollar amount) and Y (duration)

If both thresholds are satisfied, the next step is to solve for X, where X is the guideline amount of maintenance. The new provision states that the amount of maintenance shall be calculated by taking 30 percent of the payor's gross income minus 20 percent of the payee's gross income.18 There is a cap, though: when the amount of maintenance is added to the gross income of the payee, it may not result in the payee receiving more than 40 percent of the combined gross income of the parties.19

Here again, the expansive definition of gross income comes into play, both for the payor and the payee. The amount of maintenance payable after the dissolution date must be based on the guidelines unless the court finds they are inappropriate. Significantly, the guideline amount does not vary depending on the length of the marriage. In other words, the maintenance amount is presumptively the same for a one-year or a 40-year marriage. Considering existing case law, this in itself may be a reason to deviate.

Next, solve for Y, where Y is the duration of the maintenance award. The duration is calculated by multiplying the length of the marriage at the time the action was commenced by whichever of the following factors applies: 5 years or less (.20); more than 5 years but less than 10 years (.40); 10 years or more but less than 15 years (.60); or 15 years or more but less than 20 years (.80).20 For a marriage of 20 or more years, the court in its discretion will order maintenance either permanently or for a period equal to the length of the marriage.

The IMDMA rewrite answered the questions of when to measure the length of the marriage and the ambiguity that had previously existed in the overlapping brackets. But there are still a few dramatic leaps in the duration.

For example, the change from a nine- to 10-year marriage results in the length of maintenance going from 3.6 to six years, and the change from a 14- to 15-year marriage results in the length going from 8.4 to 12 years. This creates an incentive for a recipient spouse whose marriage is near those benchmarks to delay filing until reaching that one extra anniversary day.

However, the formula is not the only place the length of the marriage is invoked. Another new section of the law creates a fixed-term exception for marriages under 10 years.21 It provides that if a court grants maintenance for a fixed period at the conclusion of a case commenced before the tenth anniversary of the marriage, the court may also designate the termination date as "permanent."22

The effect of this designation is that maintenance is barred after this date. This is a major departure from existing law. This provision is discretionary and applies to both guideline and non-guideline maintenance awards for cases commenced before the tenth anniversary of the marriage. This new language is also repeated in new section 510(a-6) dealing with modification and review of maintenance awards.

Are decisions under the guidelines reviewable?

A common question under the new amendments is whether a court's determination of the duration of maintenance under the guidelines is modifiable and reviewable. The answer is "yes." Unless the parties explicitly agree otherwise pursuant to section 502(f) of the IMDMA, maintenance is modifiable under section 510 of the Act. That hasn't changed.

But the preface of Section 504(a) has been changed by the IMDMA rewrite. That section is amended to read as follows: "[T]he court may grant a maintenance award for either spouse in amounts and periods of time as the court deems just,...."23

The phrase "in gross or for fixed or indefinite period of time" was stricken from that sentence of the section (as were the words "temporary or permanent"). The stricken language had given the court discretion to order rehabilitative or reviewable maintenance, as opposed to permanent (indefinite) maintenance or maintenance in gross. Under the IMDMA rewrite, those distinctions are deleted, and the court simply has discretion to award maintenance for periods of time it deems just.

But that still begs the question of a review. The amendments did not change section 510(a-5) of the Act dealing with modification and review. But the language of section 504(b-4.5) (fixed-term exception for marriages of less than 10 years) is repeated in new section 510(a-6). Since the fixed-term option is an exception to the general rule for review, this implies that any other guideline maintenance award would still be subject to a review.

In all, with the exception of marriages of under 10 years at the time of filing, the existing rules for modification and review probably still apply in any guideline maintenance case. The issue of review under a guideline maintenance award may be a hot topic in courtrooms.

The amendments also make a significant procedural change.24 Now, in every maintenance case, the court must make specific findings and state its reasoning for awarding or not awarding maintenance, including references to each relevant maintenance factor.

This applies not just in contested hearings and trials but even in settlement agreements. Even a waiver of maintenance probably requires specific findings for not making an award. Moreover, just as with child support, if the court deviates from the guidelines it must include in its findings the amount or duration of maintenance that would have been required under the guidelines and the reason for any variance. This amendment will change how judgments, orders, and settlement agreements are drafted.

A hypothetical case

Now let's look at a common case scenario. Assume Husband's gross wages are $100,000 per year, Wife's gross wages are $25,000 per year, and the parties have two minor children. Wife has custody of them.

The individual and dependent health insurance premium paid by Husband is $600 per month, and the parties will each claim one dependent for their separate taxes. They have been married for 15 years and one day. There is no previous marriage or other "multiple family" situation. The judge has determined that maintenance is appropriate.

Strictly applying the maintenance guidelines without deviation, Husband will pay $25,000 per year in maintenance to Wife for 12 years. (By comparison, if the parties were married for 14 years, 11 months, and 30 days, the duration of maintenance would have been nine years.) The resulting guideline child support payment will be $13,884 per year. (By comparison, child support would have been $18,622 per year without the maintenance deduction from net income.)

So, on a pretax basis, Wife's total gross cash flow is $63,884, and Husband's is $61,116. But, after taxes, Wife's total net cash flow is $56,998, and Husband's is $42,910. In total, Husband is paying approximately 39 percent of his gross and 48 percent of his net income to Wife, and Wife receives 57 percent of the total combined incomes of both parties after taxes.

Unsettled questions

There may be cases in which the maintenance guidelines produce a definitive, predictable resolution, just as intended. But don't trade in your legal research subscription for a calculator just yet.

Ironically, the guidelines might unintentionally spawn more litigation of maintenance, not less. Disputes about gross income, milestone anniversaries, along with deviations from the guidelines - both as to amount and duration - are likely to keep divorce courts bustling.

How courts across the state handle cases on the fringes of the guidelines may create yet another layer of inconsistency. For example, in cases where the combined gross income is only marginally greater than $250,000, some courts might consider the guidelines to arrive at a maintenance award while others might not. The informal rules of thumb that varied from circuit to circuit, county to county, and judge to judge, may yet reemerge.

In short, the law of maintenance is sure to be a hot topic in trial courts and appellate courts this year and for years to come.

Jeffrey L. Hirsch is an associate with The Gitlin Law Firm in Woodstock. His family law practice includes litigation, mediation, collaborative law, and arbitration.

jeffrey@gitlinlawfirm.com

ISBA RESOURCES >>