ISBA Development Site

This website is for ISBA staff use only. All visitors should return to the main ISBA website.

This website is for ISBA staff use only. All visitors should return to the main ISBA website.

May 2016 • Volume 104 • Number 5 • Page 20

Thank you for viewing this Illinois Bar Journal article. Please join the ISBA to access all of our IBJ articles and archives.

Lawyers owe it to clients to thoroughly prepare witnesses to testify. On the other hand, they have a duty to be truthful and to counsel witnesses to do the same. Here are best practices for ethical-yet-effective witness preparation.

Last year, Chicago criminal defense lawyer Beau Brindley was tried in federal court for improperly coaching witnesses, having been charged with 21 criminal counts tied to that practice. He was acquitted by a judge who among other things remembered his own "exhaustive preparation" of witnesses when he was a practicing lawyer. (See The Beau Brindley case: Witness preparation v. coaching, LawPulse, November 2015 Journal.)

Last year, Chicago criminal defense lawyer Beau Brindley was tried in federal court for improperly coaching witnesses, having been charged with 21 criminal counts tied to that practice. He was acquitted by a judge who among other things remembered his own "exhaustive preparation" of witnesses when he was a practicing lawyer. (See The Beau Brindley case: Witness preparation v. coaching, LawPulse, November 2015 Journal.)

The case underscores the dilemma lawyers face in preparing witnesses. On the one hand, they owe it to their clients to thoroughly prep witnesses for what can be make-or-break testimony. On the other, they owe an ethical - indeed, a legal - duty to be truthful and not to present false evidence.

Ethical preparation starts with counseling the witness to tell the truth, but it doesn't end there. Properly preparing witnesses for a deposition or trial also means not putting words in their mouths, discouraging them from guessing or speculating, returning to the scene of the crime or accident if necessary to refresh their memories, and more, all while ensuring that enough time is left to cover all those bases beforehand.

The truth, even if it hurts

"The first and the last thing you tell either a witness or your client is: tell the truth," says David Morgans, partner at Myers, Carden & Sax in Chicago and chair of the ISBA's Standing Committee on Professional Conduct. "That's the touchstone of [everything]. A lawyer is going to get in trouble if he's done something…to elicit falsehoods."

That's the case even when the truth hurts, says Steve Corn, a retired Mattoon attorney and fellow member of the professional conduct committee. "As your parents probably told you, once you start not telling the truth, you can't remember what you said before," he says. "Litigation is about how facts apply to the law. You really can't change the facts."

The issue of telling the truth comes up in every deposition, says John Barkett, partner with Shook, Hardy & Bacon in Miami, who participated in a Professional Education Broadcast Network webcast, presented by the ISBA in January 2016, entitled Ethics of Preparing Witnesses - A National Perspective. "We all know our obligations under the rules of ethics, the Rules of Professional Conduct," he says.

In Illinois, the most directly relevant rule is 3.4(b), which says a lawyer may not "counsel or assist a witness to testify falsely, or offer an inducement to a witness that is prohibited by law." Also relevant is Rule 3.3(a)(3), which says, "If a lawyer, the lawyer's client, or a witness called by the lawyer, has offered material evidence and the lawyer comes to know of its falsity, the lawyer shall take reasonable remedial measures, including, if necessary, disclosure to the tribunal."

Also, while the fact pattern it arose out of dealt with evidence other than testimony, ISBA Professional Conduct Advisory Opinion 13-05 (May 2013) says that "[w]hen a lawyer discovers that his or her client in an administrative hearing has previously submitted false material evidence to the tribunal, the lawyer must attempt to persuade the client to correct or withdraw the false evidence, but if that fails and if the effect of the false evidence cannot otherwise be undone, the lawyer must disclose the false evidence."

Along those lines, Bruce Green, a professor at Fordham University Law School who participated in the January webcast, says if your witness says something you know is false you have to take remedial action. "Then the question becomes, what's the best way to do that without making too much of a mess of things? In the context of a deposition, it might mean pulling the client aside and saying, 'You may have misheard the question, let's go back in and correct [your answer].'"

Remember that lying on the witness stand isn't just unethical, it's a crime, Green says. And advising a witness to lie is suborning perjury. The stakes are high indeed.

Don't guess, do try to remember

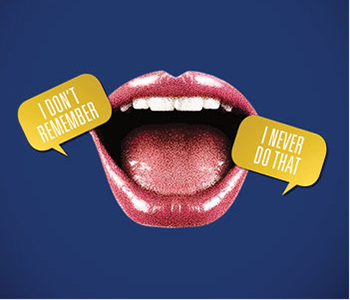

Witnesses should be discouraged from guessing or speculating or putting a guess in the guise of an estimate, Morgans says. And they should be advised about the difference between saying "I don't know" and "I don't remember."

"'I don't know' means you don't have the knowledge," he says. "'I don't remember' means you may have the knowledge, you just can't retrieve it at the time. Memory can be refreshed. The witness could be attacked on that basis on cross-examination. If it's something the witness obviously knew at one point, then [his or her] memory could be refreshed later at deposition or at trial."

For that reason, attorneys should try to refresh their witnesses' memories before opposing counsel does on less friendly terms, Morgans says, by taking steps like bringing them back to the scene of an accident.

"No witness is perfect, and rarely do two witnesses remember anything the same way," he says. "To bring the client [or witness] to the scene of an accident does tend to refresh recollections. And most importantly, it helps them understand factors of time, speed, and distance. You can go out there with a rolling tape measure so they can testify as to exact distances," decreasing the risk that the opposing attorney will trip them up.

There is also a continuum of memory - witnesses sometimes remember something but not everything about an event. Lawyers should take care not to advise witnesses to say they simply "don't remember" something if they have some recollection, Green says. In other words, be careful not to encourage witnesses to overstate the degree to which they don't remember. To do so is to encourage a witness to be untruthful.

When faced with a document-heavy case, attorneys need to make sure they show witnesses key documents so they're not seeing them for the first time when testifying, Morgans says. Yet attorneys must take care not to show witnesses any privileged documents. "Because once you do that, you waive the privilege and if the other side finds out, you might have to disclose it," he says.

Style points

Attorneys need to prepare witnesses to handle not just the substance but also the stylistic aspects of their appearances at deposition or trial, Morgans says.

For starters, witnesses should be admonished not to argue, swear, use pejoratives, or otherwise be impolite, he says, and they should be warned not to use superlatives or unequivocal statements like "I never do that," which beg to be disproven in dramatic fashion.

"Those things can be poison later in dep or at trial," he says. "You have to remind them that they only need to answer the question that's asked." If they don't understand the question, they should say they don't understand, Morgans says.

And be careful that they don't mindlessly fill the empty space when opposing counsel is silent, he says. "I've had witnesses go on and on, and sometimes you have to say, 'You've answered the question.'" Offering unnecessary information is distracting at best and could even damage your case.

Witnesses too often try to "play attorney" and figure out what a question from opposing counsel is intended to do, then give an answer they think is best for the case, Corn says. "It's not good for the witness to try to steer the testimony," he says.

Instead, witnesses should be advised to truthfully answer only the question that was asked, he says. Tell them you as the lawyer can use further questions or other means to make sure issues are brought out as necessary.

Witnesses and clients should let the other attorney finish the question, and if they don't understand it, simply say so. Witnesses should not try to answer a question they don't understand. Instead leave it to the other lawyer "to rephrase it or ask a different question," Corn says.

Corn and Morgans agree that witnesses should be warned not to argue with opposing counsel. They should also take care to take the deposition or trial seriously, Morgans says. "Tell them not to make jokes," he says. "Don't use sarcasm. That can look bad on the transcript when it comes out."

At the same time, attorneys need to prepare witnesses to be firm if the questioner becomes impolite to them and, for example, cuts them off in mid-sentence, Morgans says - and you as lawyer should be prepared to jump in if your witness lacks the strength or sophistication to respond appropriately to abrupt or aggressive questioning.

"Sometimes, the first half of the answer will sound good to the questioner, and he will cut them off - and sometimes you have to jump in and say, 'Let [my witness] answer the question,'" Morgans said.

Their words, not yours

In preparing a witness to interact with opposing counsel, be absolutely certain not to put words in a witness's mouth, Morgans says, even if you're tempted.

"There are many different ways to express the same thing, and you want to make sure the witness' testimony is understandable," he says. "Sometimes you do tell them, 'Are you sure it's not more like 'this' than 'that'? What you need to do to prepare a witness is basically cross-examine them [so they're] prepared for the questions that come up."

But take care not to exert too much control in the preparation, Morgans says. "You don't want them to look too staged or rehearsed," he says. "You want them to use their natural language.

"Different people use different lingo or idioms, and you have to live with that. But if the witness or client is describing something, and you think it's unclear or offensive, you can challenge them on it. Sometimes they will stick to their guns. Other times they will say, 'Yes, there's a more polite way of saying it."'

Just make sure you don't go overboard, he says. "Don't say, 'Here's the story, and here's how you're going to tell it.'"

Suppose the trial has started and testimony is underway - can you offer advice at break when your witness, who is still under oath, asks, "How am I doing?"

Barkett says there are two lines of authority in federal court. "One says you may not consult," except to advise the witness about whether specific information is privileged and should not be shared, he says. "The other says your duty is to your client," which means you're free to talk to the witness when it serves that end, as long as you don't coach about specifically what to say. (For a local perspective on the federal law, see "But we were on a break…" in the June 2014 issue of The Public Servant, newsletter of the ISBA Standing Committee on Government Lawyers).

Time and money - witness preparation and compensation

Build in time for prep. To touch all of these bases, attorneys must ensure they allow enough time for witness prep, especially for a complex case, Morgans says. That means attorneys need to consider the sophistication of a witness. Some will need more preparation than others.

"Let's say you have a big commercial case and a lot of money riding on it," he says. "You're going to want to explain to [the witness], in some detail sometimes, not just the applicable law but how the law impacts the facts, and vice versa.

… Sometimes you have to start preparing them months in advance.

"If someone knows the facts and the case is simple enough, you can prep them for a few hours a couple weeks before [they testify], and that's all you do," Morgans says. "But other people require numerous sessions, sometimes focusing on one set of documents or one aspect of the case, and then another session on another aspect."

The length of time and number of sessions spent depends on the witness's sophistication and the type of case, Corn agrees. "My suggestion is always to have at least two preparation sessions: the first meeting to go over surface issues and the second to go over the specifics of what areas are going to be asked [and to hear] what the answer might be -but not telling them what their answer is going to be," he says.

They also need to think about how they appear when they aren't on the stand, Corn says. "I tell them, at trial there's always going to be one juror looking at you the entire time," he says. Above everything, "don't fall asleep. You need to stay awake, even if it's the third day at trial, it's warm in the courtroom, and you just had lunch. Plus you shouldn't scoff, and you shouldn't make faces."

Paying lay witnesses? Expert witnesses are typically paid for their time, expenses, and expertise. But what about lay or "fact" witnesses - can they be paid as well? Ethics opinions are unclear as to exactly how far you can go, Morgans says.

Clearly the pay may not constitute an "inducement" to the witness to favor your side, which is prohibited by Rule 3.4(b). But Morgans says it's typically OK to pay them for reasonable travel expenses and lost work time. "It's an individual thing" and depends on the circumstances, he says. "It's a pretty fluid practice."

The issue of when an attorney can or can't pay a witness "is a very significant topic," Barkett says. He cites ABA Ethics Opinion 96-402 for the proposition that fact witnesses can be reimbursed at a reasonable rate for their time and expenses as long as the payment isn't conditioned on the content of their testimony.

Ed Finkel is an Evanston-based freelance writer.

edfinkel@earthlink.net