ISBA Development Site

This website is for ISBA staff use only. All visitors should return to the main ISBA website.

This website is for ISBA staff use only. All visitors should return to the main ISBA website.

August 2017 • Volume 105 • Number 8 • Page 44

Thank you for viewing this Illinois Bar Journal article. Please join the ISBA to access all of our IBJ articles and archives.

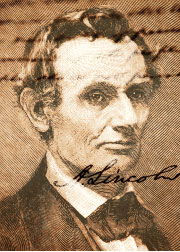

In his "Notes for a Law Lecture," Lincoln left us a blueprint for good lawyering. His advice is echoed in case law and the Illinois Rules of Professional Conduct.

What does it mean to be a "Lincoln Lawyer"? It turns out that Lincoln left his own thoughts on the matter. In his "Notes for a Law Lecture,"1 believed to have been written in 1850, Lincoln wrote that the good lawyer is among other things diligent, moral, a good businessman, and above all honest. In this column we'll focus on two qualities: diligence and encouraging alternatives to trial. (Find out about and register for the Lincoln Legacy CLE program, coming up September 8 in Lincoln.)

Our modern Rules of Professional Conduct mirror all of the significant points of Lincoln's thoughts and stand as Lincoln guideposts. Cases from Lincoln's career illustrate what the Lincoln Lawyer should aspire to today.

Diligence

There are many examples of "diligence" in Lincoln's practice, but perhaps the best is from one of the major trials of his career, Hurd v. Rock Island Bridge Company, commonly known as the Effie Afton Case. The case was tried in the federal district court in Chicago in September 1857. It was a classic confrontation between competing modes of transportation -waning river transport and the up-and-coming railroads.

Lincoln represented the bridge company, which completed this bridge across the Mississippi at Rock Island in April 1856. The first train crossed April 21. On May 6, The Effie Afton crashed into the bridge and was destroyed by the resultant conflagration. Hurd, the boat's owner, sued for obstruction of the river.

Lincoln demonstrated diligence in his trial preparation by visiting the site. He hired a boat to pass under the bridge to study the currents. He also floated debris past the site. Thorough preparation included proof that over the 11-month period before the trial, 12,386 freight cars and 74,179 passengers had passed over the bridge, underscoring its importance.

The 15-day trial resulted in a hung jury, which favored the railroad 9 to 3. The case was never retried.

The Illinois Rules of Professional Conduct (IRPC) reflect today's concept of "diligence." IRPC 1.1 reminds that "a lawyer shall provide competent representation to a client. Competent representation requires the legal knowledge, skill, thoroughness and preparation reasonably necessary for the representation." IRPC 1.3 says "a lawyer shall act with reasonable diligence and promptness in representing a client."

A modern example reflects the failure to meet the Lincoln Lawyer standard of diligence. In Campbell v. Reardon, 780 F.3d 752 (7th Cir. 2015), the defendant was convicted of murder for participating in a mob beating in Champaign on Christmas day 1997. He maintained his innocence and complained of the efforts of his appointed trial counsel.

Three witnesses testified for the prosecution that the defendant had sold the victim fake drugs and then was part of a group of men that beat the victim. The victim later died. The prosecution witnesses had extensive criminal records and evidence placed them in the group of people responsible for the beating.

Trial counsel did not interview other witnesses who would testify that defendant was not one of the men in the group, and in fact was identified as being nearby but not involved in the beating at all. The seventh circuit remanded the case for a habeas corpus hearing that led to the grant of the writ and the defendant's eventual exoneration.2 The contemporary Lincoln Lawyer is prepared, knows the facts and the law, and effectively presents the client's case at trial.

Discouraging litigation

Lincoln's notes reflect that the good lawyer looks for ways to resolve disputes short of trial. He wrote that the "nominal winner is often a real loser - in fees, expenses, and waste of time." In this fashion the good lawyer should be a "peacemaker," he wrote.

One of Lincoln's most bizarre cases was the defamation case of Spink v. Chiniquy. Chiniquy was a French-Canadian priest sent from Quebec to the French-Canadian communities in southern Kankakee and northern Iroquois Counties. Chiniquy repeatedly stated from the pulpit that Spink had perjured himself on numerous occasions, defaming Chiniquy.

After Spink was cleared of the charges, he sued the volatile, eccentric priest and received a change of venue to Champaign County, where the case was first tried in May 1856. The three-day trial resulted in a hung jury. A mistrial was declared and the case was reset for trial in Urbana in October.

In that interim Lincoln made a real effort to get his client to settle, but the self-righteous Chiniquy steadfastly refused. Finally, right before the re-trial, Lincoln persuaded him to recant his slanderous remarks. He did so by signing a document in Lincoln's hand stating he never believed Spinks to be guilty of perjury.3

Illinois Rules of Professional Conduct provisions show that little has changed in the propriety of law practice between Lincoln's time and now. IRPC 3.1 directs a lawyer to not "bring or defend a proceeding, or assert or controvert an issue, unless there is a basis in law and fact for doing so." IRPC 3.2 advises the practitioner to "make reasonable efforts to expedite litigation consistent with the interests of the client." Thus, the Lincoln Lawyer keeps unworthy disputes out of court and moves worthy ones along as quickly as possible.

Guy Fraker is a retired attorney from Bloomington. He is the author of Lincoln's Ladder to the Presidency: The Eighth Judicial Circuit and other Lincoln articles and books.

J. Steven Beckett is an of-counsel attorney with Beckett & Webber PC in Urbana and the retired director of trial advocacy at the University of Illinois College of Law.