ISBA Development Site

This website is for ISBA staff use only. All visitors should return to the main ISBA website.

This website is for ISBA staff use only. All visitors should return to the main ISBA website.

This article is part one of a three-part series.

“Are we our brother’s keeper?” This centuries old question typically is intended to challenge us to think about how we view ourselves and society at large. People will respond differently based on their individual values and experiences. Despite the wide range of personal views that make up our country, in the United States the answer to this question is a resounding yes, but not in the sense typically understood.

![]() This article looks at incarceration and other correctional supervision in the U.S.1 The idea for this article originated when the author came across figure 1, stating: “1 out of 5 prisoners in the world is incarcerated in the U.S.” This assertion raised more questions than answers and started a chain of inquiry.

This article looks at incarceration and other correctional supervision in the U.S.1 The idea for this article originated when the author came across figure 1, stating: “1 out of 5 prisoners in the world is incarcerated in the U.S.” This assertion raised more questions than answers and started a chain of inquiry.

As legal professionals, we are in the unique position of being immersed in the inner workings of the law. We routinely research, interpret, explain, argue, and defend the law. We may not always agree, but we still respect the rule of law.

But law is not static and neither is society. As conscientious citizens, as well as legal professionals, we need to step back from time to time to see the larger picture. Is the law and its enforcement serving us well? Is it written, interpreted, and enforced in a fair and balanced way taking into account all constituencies?

Crime and criminal justice are complex issues. What we as a society treat as a crime, the criminal corrections systems we adopt, and how we respond to our fellow citizens and residents are choices we collectively make. These choices are not static and change over time. The author’s hope is that this series of articles will help you participate in that decision-making process and add your voice to the mix, consistent with your values and experiences.

The U.S. does not have one criminal justice system. As the authors of Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie 2020 explain: “The American criminal justice system holds almost 2.3 million people in 1,833 state prisons, 110 federal prisons, 1,772 juvenile correctional facilities, 3,134 local jails, 218 immigration detention facilities, and 80 Indian Country jails[,] as well as in military prisons, civil commitment centers, state psychiatric hospitals, and prisons in the U.S. territories.”2 These disparate systems adopt and implement different policies and procedures, have differing accountability, and track information differently. Data is not always timely produced or analyzed and is not always comparable.

Further, how one chooses to slice the data has a significant effect on how the data is interpreted and utilized. The U.S. Department of Justice (“DOJ”) cautions that: “Changes in [data] are always evaluated within the context of time, and changing that context—[by] selecting a different subset of years [or data sources]—influences whether [the trend] appears to be increasing or decreasing…Without a longer trajectory, year-to-year changes in data seem like emerging trends.3

“Distinguishing stable trends from temporary fluctuations is essential to understanding how crime is affected by changes in criminal justice policy, as well as by varying social, economic, and demographic influences,”4 explains author John J. Donahue in his article, Understanding the Time Path of Crime, published in the Journal of Criminology (italics added).

Based on 2019 data, the U.S. had just over 4 percent5 of the world’s population but accounted for approximately 22 percent of the world's known prison population (see figure 1 above).6

This data raises many questions, including:

Beyond just a global comparison, this article will also look at other factors that contribute to incarceration in the U.S.—some will surprise you. A review of our misdemeanor, probation, and parole systems leads to interesting insights into our use of corrections and incarceration in the U.S.

The U.S. National Research Council in 2014 concluded that:

“The growth in incarceration rates in the United States over the past 40 years is historically unprecedented and internationally unique.”7

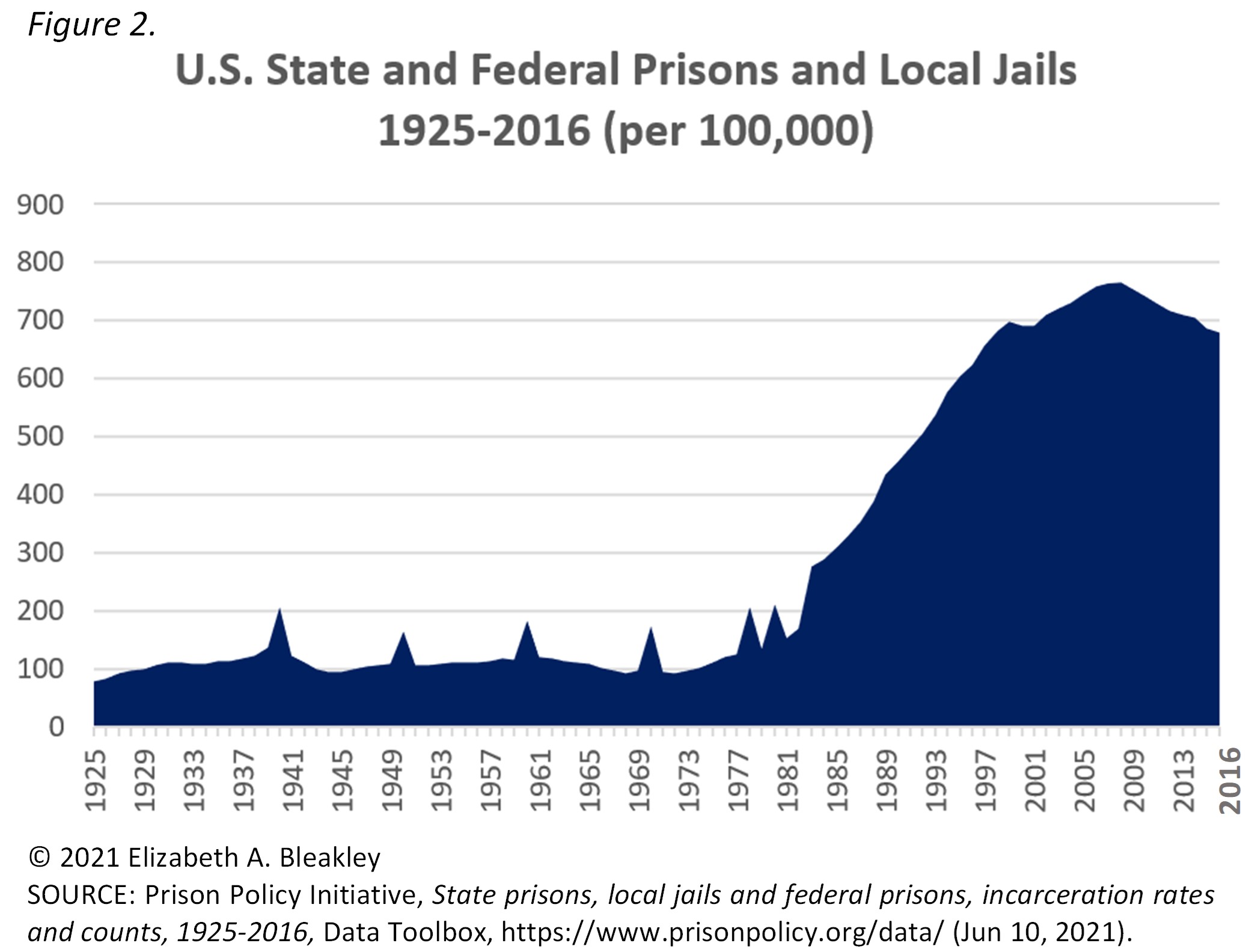

The U.S. incarceration rate was apparently relatively stable from at least the 1920’s through the early 1970’s. Then the incarceration rate rose rapidly for decades (see figure 2).8 The American Conservative Union Foundation, in its 2018 letter to Congress asserted that:9

“Between 1980 and 2013, our federal prison population jumped nearly 800 percent….The average length of federal sentences has doubled during the same period. Not surprisingly, prison costs have also skyrocketed….[T]he Department of Justice's Inspector General has called these increasing expenditures for prisons "unsustainable."10

This bleak picture is the result of multiple complex and interrelated factors that do not lend themselves to easy answers or simple solutions. Is the increase a result of escalating crime, the overuse of incarceration as a corrections method, or a combination of multiple other factors? Some reduction in these statistics has been seen in recent years, though not of the same magnitude as the decades-long escalation. Article three of this series will take a closer look at crime statistics and correlation.

According to several sources, possible reasons for America’s (comparatively) high levels of incarceration include:

![]() The U.S. homicide rate is a significant outlier when compared to certain Western countries like Australia, Spain, and the United Kingdom. Figure 3 shows the comparative trends from 1950 through 2010. The U.S. is the top trendline, and consistently has the highest homicide rates over time.

The U.S. homicide rate is a significant outlier when compared to certain Western countries like Australia, Spain, and the United Kingdom. Figure 3 shows the comparative trends from 1950 through 2010. The U.S. is the top trendline, and consistently has the highest homicide rates over time.

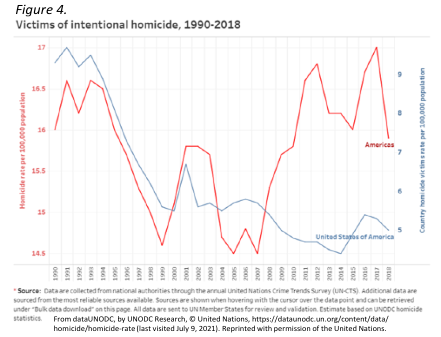

But compare the homicide rate in the U.S. to other regions of the world, and the picture looks very different. Figure 4 shows the homicide rates from 1990 through 2018 for the Americas (red) and for the U.S. (blue). In the Americas, the rate was 16.0 in 1990 and 15.9 in 2018, while in the U.S. the rate was 9.3 in 1990 and dropped to 5.0 by 2018.

As of 2018, the U.S. homicide rate was overshadowed by countries like Venezuela, the Bahamas, and Honduras.

Viewed in this way, lethal crime does not appear likely to be a significant factor in the U.S.’s high incarceration rate relative to the rest of the world.

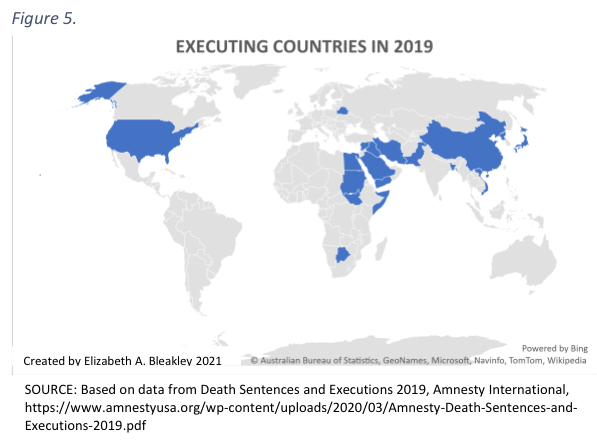

Amnesty International reports 657 executions by judicial use of the death penalty were carried out globally in 2019 (see figure 5):15

Amnesty International reports 657 executions by judicial use of the death penalty were carried out globally in 2019 (see figure 5):15

Most executions took place in China, Iran (251+), Saudi Arabia (184), Iraq (100+), and Egypt (32+). Excluding China, the other four countries were responsible for 86 percent of such executions.

“As in previous years, the global recorded totals do not include the thousands of executions that Amnesty International believe[s] were carried out in China, where data on the death penalty is classified as a state secret.”

In the U.S., 22 prisoners were executed in seven states in 2019.16 This placed the U.S. in sixth place for known executions under sentence of death worldwide and the only such executioner in the Americas region for the 11th consecutive year, according to Amnesty International. But many of the countries lower on the list lack sufficient information to provide credible numbers, including North Korea, Syria, and Vietnam.

The high number of executions in certain other countries does appear to contribute significantly to their lower incarceration rates, relative to the U.S.17

In 2017, the International Center for Transitional Justice (“ICTJ”), observed an “alarming rise in the incidence of enforced disappearances around the world, particularly in a number of the "Arab Spring" states, such as Syria, Egypt and Yemen.”18 According to the ICTJ, Syria experienced the enforced disappearance of over 65,000 people, including entire families and thousands of children.19

China reportedly detains individuals and holds them at undisclosed locations for extended periods, including mass detention of Uighurs, ethnic Kazakhs, and other Muslims in Xinjiang.20

“There are few crimes as chilling as enforced disappearances. There is no closure for the families or loved ones, as hope mixes with fear. Families suffer and often find themselves without a breadwinner and difficulty obtaining any support or benefits (as they cannot prove the death of the one disappeared).”21

Secret prisons where officials forcibly “disappear people” are known as “no-return prisons.”22 Such disappearances and no-return prisons do reduce the number of reported incarcerations of certain other countries when compared to the U.S.

In 2017, The Sentencing Project found that nearly one of every nine people in prison in the U.S. was serving a life sentence, and a significant number of others were serving “virtual life” sentences of 50 years or more.23 This represented 13.9 percent of the prison population at the time, or one of every seven people behind bars.24 According to the Brennan Center for Justice, 83 percent of the world’s population of life-without-parole prisoners is incarcerated in the U.S.25

In his work, Incarceration Rates in an International Perspective, Marc Mauer found a “striking” variation in the length of prison sentences across countries and its effect on overall rates of incarceration.26 Mauer cites a prior study that found “the United States generally imposes longer sentences on persons sentenced to incarceration than other industrialized nations.”27 The Institute for Crime & Justice Policy Research published an interesting report in 2021 on sentencing practices for ten countries with disparate circumstances and policy approaches across five continents.28

Sentence length in the U.S. does appear to have a significant impact on our relatively high incarceration rates.

In 2015, “Black people [were] nearly six times as likely to be incarcerated as [W]hite people, and nearly three times as likely to be incarcerated as their Latino counterparts[,]” according to the author of Mass Incarceration in America.29 In his 2020 study, author Steven Elías Alvarado found that “discrimination…is a part of blacks’ daily lives, regardless of socioeconomic background,” and “residential mobility for blacks does not protect against incarceration as much as it does for whites and Latinos.”30

Some scholars maintain that mass incarceration in the U.S. can only be understood in conjunction with the history of African Americans over several centuries.31 According to author Ta-Nehisi Coates,32 “peril is generational for black people in America—and incarceration is our current mechanism for ensuring that the peril continues.” He contends that incarceration “was the method by which we chose to address the problems…resulting from ‘three centuries of sometimes unimaginable mistreatment’ [of black people].33

Internationally, poor and marginalized communities are overrepresented in prisons “across the board[,]” according to the authors of Prison, Evidence of its use and overuse from around the world.34 With respect to race and ethnicity, the authors point out that:

Race and ethnicity do significantly impact the number of people incarcerated in the U.S.; however, this phenomenon is seen in many other countries, as well. The relative impact compared to other countries is unclear.

In its 2018 report to the United Nations, The Sentencing Project asserted that disparities in the U.S. criminal justice system are “deeper and more systematic than explicit racial discrimination”:

The United States in effect operates two distinct criminal justice systems: one for wealthy people and another for poor people and people of color. The wealthy can access a vigorous adversary system replete with constitutional protections for defendants. Yet the experiences of poor and minority defendants within the criminal justice system often differ substantially from the model.”37

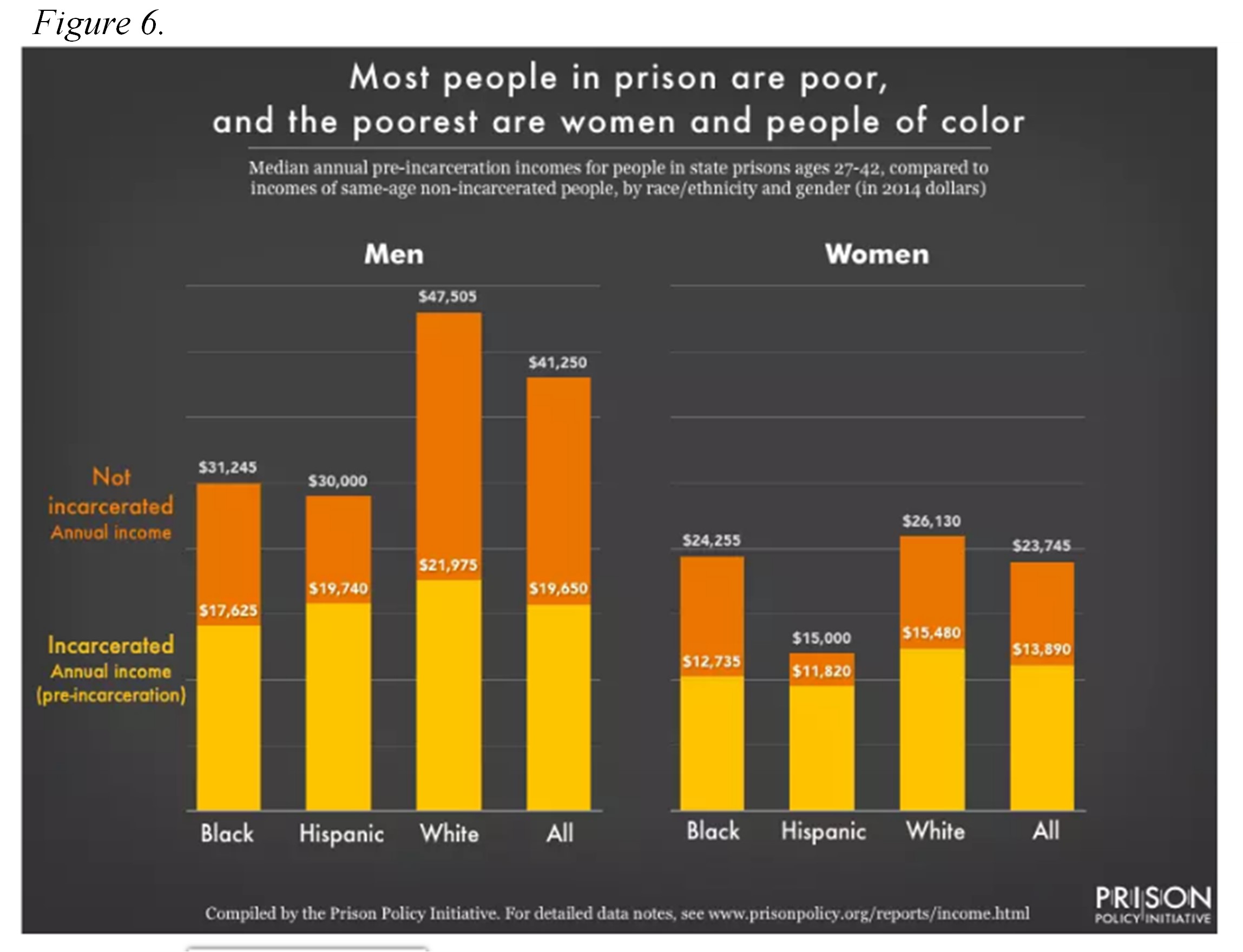

People in prison and jail are disproportionately poor compared to the overall U.S. population38 (see figure 6). “Poverty is not only a predictor of incarceration[39]; it is also frequently the outcome, as a criminal record and time spent in prison destroys wealth[40], creates debt, and decimates job opportunities[41 ].”42 Mass incarceration and hyper-criminalization serve as major drivers of poverty.”43

People in prison and jail are disproportionately poor compared to the overall U.S. population38 (see figure 6). “Poverty is not only a predictor of incarceration[39]; it is also frequently the outcome, as a criminal record and time spent in prison destroys wealth[40], creates debt, and decimates job opportunities[41 ].”42 Mass incarceration and hyper-criminalization serve as major drivers of poverty.”43

In 2016, the U.S. DOJ Office for Access to Justice published a brief to “advance[] the department’s robust efforts to prevent unlawful practices that punish poverty at every stage of the justice system and that trap vulnerable residents in cycles of debt from court fines and fees.”44

“The criminal justice system punishes poverty, beginning with the high price of money bail: The median felony bail bond amount ($10,000) is the equivalent of 8 months’ income for the typical detained defendant.”45

Internationally, “those entering pretrial detention come from the poorest and most marginalized echelons of society, who are least equipped to deal with the criminal justice process and the experiences of detention.”46 According to Salla and Rodriguez Ballesteros,“[i]ndependent research and government data consistently show that in both high income and low income economies, those who are held in pretrial detention are…more likely to lack the means to secure non-custodial options, including bail.”47 “In the African states[,] as in India, the prosecution of petty offences results in excessive use of imprisonment (including through unnecessary and lengthy pre-trial detention). Excessive imprisonment “takes a disproportionate toll on poor communities and acts as a brake on development.”48

Poverty does contribute significantly to the number of people incarcerated in the U.S.; however, this phenomenon is also seen in many other countries. As with race and ethnicity, the relative impact of poverty compared to other countries is unclear.

Countries have their own unique histories, cultures, and values. These differences inform the criminal justice systems adopted by each country, including the United States. Comparisons of such systems do not lend themselves to easy answers but do provide insights and alternatives, as well as challenge some of our assumptions.

Criminal convictions include both felonies and misdemeanors. A felony is a serious crime punishable by more than a year in prison or by death. A misdemeanor is a “lesser crime,” punishable by a fine or jail time of up to one year. To be clear, a misdemeanor is still a crime.49

Misdemeanors far outnumber felonies. Approximately 13 million misdemeanor charges were filed in 2015 alone, according to legal scholar and author Alexandria Natapoff, who found that “the [misdemeanor] system is 25 percent bigger than we thought it was, and four times the size of the felony system.”50

Sometimes misdemeanors don’t even look much like crimes. In twenty-five states, speeding is a misdemeanor. Loitering, spitting, disorderly conduct, and jaywalking belong to a large group of crimes called “order-maintenance” or “quality-of-life” offenses, and they make it a crime to do unremarkable things that lots of people do all the time. By contrast, some misdemeanors are quite serious—drunk driving and domestic assault for example.51

In state courts, just over half (54 percent) of people charged with misdemeanors went to jail and 22 percent were sentenced to probation, according to BJS state statistics released in 2010.52 In federal courts, approximately 62 percent of misdemeanor defendants were convicted, of which approximately 36 percent were incarcerated, 34 percent were given probation, and 21 percent were given fines only.53

In Punishment without Crime, author Natapoff explains that “[i]n federal courts[,] which have smaller caseloads and more resources, indigent defendants charged with shoplifting or DUI get skilled counsel, and courts routinely hold hearings and proper trials.”54

Unfortunately, Natapoff found that in many state courts misdemeanor cases are resolved by guilty pleas with as little as one to three minutes spent in court, in large part without the benefit of legal counsel:

This dynamic not only contradicts numerous fundamental legal rules, it also invites wrongful conviction: innocent people arrested for low-level offenses routinely plead guilty to crimes they did not commit….Innocent people might [plead guilty] because they are too poor to pay bail…meaning that they will remain in jail for weeks or even months until their cases are over.55

Two U.S. Supreme Court cases help to bring concerns related to misdemeanors into focus:

In Justice Souter’s concurring opinion in Nichols v. United States,56he raised studies previously considered by the Supreme Court57 that show "the volume of misdemeanor cases . . . may create an obsession for speedy dispositions, regardless of the fairness of the result."

In Atwater v. Lago Vista,58the U.S. Supreme Court held that the Fourth Amendment does not forbid a warrantless arrest for a minor criminal offense, such as a misdemeanor seatbelt violation punishable only by a fine. Ms. Atwater was arrested in front of her small children, booked, and placed in a jail cell, then taken before a magistrate and released on bond, all over a seatbelt misdemeanor for which she ultimately paid a $50 fine.

Community supervision is often seen as a “lenient” punishment or an “ideal “alternative” to incarceration.59 In Bearden v. Georgia, the U.S. Supreme Court stated that the decision to place a defendant on probation reflects a determination by the sentencing court that imprisonment is not required.60

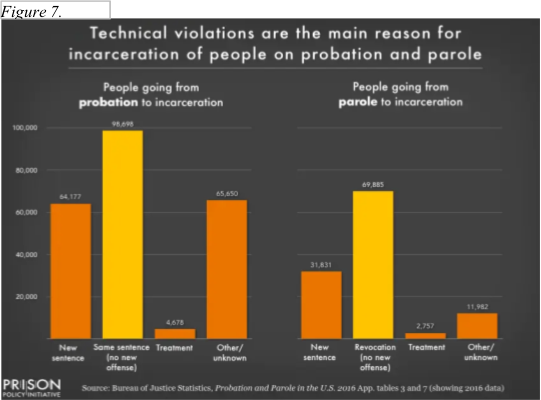

In reality, probation and parole frequently lead to incarceration (see figure 7). According to a 2020 publication by the Prison Policy Initiative, the conditions of community supervision are commonly so restrictive that they “result in frequent ‘failures,’ often for minor infractions like breaking curfew or failing to pay unaffordable supervision fees.”61

In reality, probation and parole frequently lead to incarceration (see figure 7). According to a 2020 publication by the Prison Policy Initiative, the conditions of community supervision are commonly so restrictive that they “result in frequent ‘failures,’ often for minor infractions like breaking curfew or failing to pay unaffordable supervision fees.”61

Vincent Schiraldi, a former NYC Probation Commissioner and Senior Advisor to the NYC Mayor’s Office of Criminal Justice, explains that while probation was “[e]stablished originally as an alternative to incarceration, probation has grown too large for jurisdictions to adequately fund and has become a major contributor to mass incarceration.”62 He points out that, as of 2017, probation and parole were supervising more than twice as many people as were in all of America's prisons and jails.

Supervised individuals often are impoverished, yet have to pay probation supervision fees, court costs, test fees, and electronic monitoring fees, among a myriad of other fees.63 “Criminal justice debt ensures that people who are no threat to public safety remain enmeshed in the system,” according to the authors Patel and Philip.64 Roughly one-quarter of the respondents in Harris and colleagues’ 2010 study served time in jail for nonpayment of fees and fines; another study found that 12 percent had been re-incarcerated for missing payments.65 The authors of Criminal Justice Debt assert that “[t]his limited perspective results in senseless policies that punish people for being poor, rather than generate revenue.”66

In Bearden v. Georgia, the U.S. Supreme Court weighed in on this issue:

We hold, therefore, that in revocation proceedings for failure to pay a fine or restitution, a sentencing court must inquire into the reasons for the failure to pay. … If the probationer could not pay despite sufficient bona fide efforts to acquire the resources to do so, the court must consider alternative measures of punishment other than imprisonment. … To do otherwise would deprive the probationer of his conditional freedom simply because, through no fault of his own, he cannot pay the fine. Such a deprivation would be contrary to the fundamental fairness required by the Fourteenth Amendment.67

In Shackled to Debt, the authors explain that “as assessed and administered in the U.S., CJFOs [criminal justice financial obligations] can be quite punitive and insufficiently parsimonious. In those instances, their administration challenges even basic notions of citizenship rights and social justice.”68

This is the first article of a three-part series.

Please see “Are We Our Brother’s Keeper?” Part 2: Incarceration, Criminal Records, and Collateral Consequences for a look at these issues.

Please see “Are We Our Brother’s Keeper?” Part 3: Reconsidering Crime and Corrections for a look at incarceration and crime rates, correlation, and reconsidering corrections.

Elizabeth Bleakley is the managing principal at Bleakley Law LLC, Chicago, which focuses on corporate, securities, estate, and probate law. She is past Chair of the ISBA Business and Securities Law Council and the ISBA Business Advice and Financial Planning Council. Elizabeth is a former ABA Business Law Fellow. Elizabeth would like to thank the following people for their contributions and insights to this article: Daniel Edelstein, Melanie Kanakis, and Michael Bucci.

1. “Corrections” refers to the supervision of persons arrested for, convicted of, or sentenced for criminal offenses. “Correctional supervision” includes incarceration in prison or jail (“institutional corrections”) and probation and parole (“community corrections”). Corrections Data, Bureau of Justice Statistics (“BJS”), https://bjs.ojp.gov/topics/corrections (accessed Jun 25, 2021). Corrections data, with a few exceptions, covers adult agencies or facilities and adult offenders. https://bjs.ojp.gov/topics/corrections ; https://bjs.ojp.gov/data-collection/national-prisoner-statistics-nps-program ; E. Ann Carson, National Prisoner Statistics (NPS) Program (1926-Present) Bureau of Justice Statistics, https://bjs.ojp.gov/data-collection/national-prisoner-statistics-nps-program (accessed Jun 8, 2021).

2. Wendy Sawyer & Peter Wagner, Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie 2020, Prison Policy Initiative, (Mar 24, 2020), https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2020.html (accessed Jun 8, 2021).

3. U.S. DOJ Office for Victims of Crime, Crime Trends, National Crime Victims’ Rights Week Resource Guide: Crime and Victimization Fact Sheets (2018), https://ovc.ojp.gov/sites/g/files/xyckuh226/files/ncvrw2018/info_ flyers/fact_sheets/2018NCVRW_CrimeTrends_508_QC.pdf (accessed Jun 8, 2021).

4. John J. Donohue, Understanding the Time Path of Crime, Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology Vol. 88, Iss. 4 (Summer 1998), https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/231032949.pdf (accessed Jun 8, 2021).

5. World Population Review, World Population by Country (2021), https://worldpopulationreview.com/ (accessed Jun 8, 2021).

6. German Lopez, Mass Incarceration in America, Explained in 22 Maps and Charts, VOX (2015), https://www.vox.com/2015/7/13/8913297/mass-incarceration-maps-charts (accessed Jun 14, 2021).

7. National Research Council, The Growth of Incarceration in the United States: Exploring Causes and Consequences, (Jeremy Travis, Bruce Western & Steve Redburn eds., 2014) https://www.nap.edu/catalog/18613/the-growth-of-incarceration-in-the-united-states-exploring-causes (accessed Jun 28, 2021).

8. Jail statistics were only reported for periodic intervals in the early and mid-1960s, resulting in the “spikes” in the figure.

9. David H. Safavian, Esq., Letter to Congress, American Conservative Union Foundation (Feb 7, 2018), https://bobbyscott.house.gov/sites/bobbyscott.house.gov/files/ACU%20Letter.pdf (accessed Jun 28, 2021). David H. Safavian is the Deputy Director, Center for Criminal Justice Reform, American Conservative Union Foundation.

10. Id.

11. German Lopez, The U.S. Incarcerates Too Many People – But Comparisons with Europe are Flawed, Vox, (Apr 7, 2015) https://www.vox.com/2015/4/7/8364263/us-europe-mass-incarceration (accessed Jun 18, 2021).

12. World Report 2014: China, Events of 2013, Human Rights Watch (2014), https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2014/country-chapters/china-and-tibet# (accessed Jun 18, 2021); Amnesty International, China: Human Rights Violations in the Name of “National Security,” 31st session of UPR Working Group (Nov. 2018), https://www.amnesty.org/download/Documents/ASA1783732018ENGLISH.pdf (accessed Jun 30, 2021) (The authorities increasingly use “residential surveillance in a designated location”, a form of secret incommunicado detention formalized in law in revisions to the Criminal Procedure Law in 2012.)

13. Lopez, Mass Incarceration in America, supra note 6.

14. Marisa Omori and Nick Peterson, Institutionalizing inequality in the courts: Decomposing racial and ethnic disparities in detention, conviction, and sentencing, Criminology, Vol. 58, Issue 4, p. 678-713, 09/24/2020, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/1745-9125.12257 (accessed 07/17/21).

15.Amnesty International, Death Sentences and Executions, Amnesty International Global Report 2019, https://www.amnesty.org/download/Documents/ACT5018472020ENGLISH.PDF (accessed Jun 15, 2021); Amnesty International, Death Penalty in 2019: Facts and Figures, (Apr 21, 2021), https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2020/04/death-penalty-in-2019-facts-and-figures/ (accessed Jun 17, 2021).

16. Tracy L. Snell, Capital Punishment, 2019 – Statistical Tables (June 2021), https://bjs.ojp.gov/library/publications/capital-punishment-2019-statistical-tables (accessed on 07/11/21). See also Death Penalty Information Center, State By State (2021), https://deathpenaltyinfo.org/state-and-federal-info/state-by-state (accessed Jun 15, 2021) (As of 2021, in the U.S. there are 27 states with the death penalty and 23 states without the death penalty; three states have moratoria).

17. Reality Check Team, Death Penalty: How Many Countries Still Have It?, BBC News (Dec 11, 2020), https://www.bbc.com/news/world-45835584 (accessed Jun 17, 2021).

18. David Tolbert, To Prevent Enforced Disappearances, Rethink the Justice and Security Equation, International Center for Transitional Justice, Aug. 29, 2017, https://www.ictj.org/news/prevent-enforced-disappearances-rethink-justice-and-security-equation (accessed 11/11/21).

19. Id.

20. U.S. Dept. of State, Country Report on Human Rights Practices 2018 – China (includes Tibet, Hong Kong, and Macau), https://www.ecoi.net/en/document/2004237.html, original link https://www.state.gov/j/drl/rls/hrrpt/2018/eap/289037.htm (accessed 11/11/21).

21. Tolbert, To Prevent Enforced Disappearances, supra note 18.

22. Id.

23. Ashley Nellis, Still Life: America’s Increasing Use of Life and Long-Term Sentences, The Sentencing Project (May 3, 2017), https://www.sentencingproject.org/publications/still-life-americas-increasing-use-life-long-term-sentences/ (accessed Jun 15, 2021). (Methodology: “The data in this report come directly from the state and federal departments of corrections. We first contacted research divisions within the state and federal departments of corrections in January 2016).

24. Id.

25. Andrew Cohen, The American ‘Punisher’s Brain,’ Brennan Center for Justice, May 17, 2021, https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/analysis-opinion/american-punishers-brain (accessed 07/24/21).

26. Marc Mauer, Incarceration Rates in an International Perspective, The Sentencing Project, Jun 28, 2017 https://www.sentencingproject.org/publications/incarceration-rates-inter... (accessed 07/25/21).

27. Citing Lynch, J., & Pridemore, W. (2011). Crime in international perspective. In J. Q. Wilson & J. Petersilia (Eds.), Crime and public policy (pp. 5–52). New York: Oxford University Press, https://oxfordre.com/criminology/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264079.001.0001/acrefore-9780190264079-e-233#acrefore-9780190264079-e-233-bibItem-0042 (accessed 07/25/21).

28. Catherine Heard and Jessica Jacobson, Sentencing Burglary, Drug Importation and Murder, Evidence from Ten Countries, ICPR Birbeck University of London Jan. 2021, https://www.prisonstudies.org/sites/default/files/resources/downloads/sentencing_burglary_drug_importation_and_murder_full_report.pdf (accessed 07/24/21).

29. Lopez, Mass Incarceration in America, supra note 6. See also E. Ann Carson, Prisoners in 2019, US DOJ OJP BJS, Oct. 2020, NCJ255115, https://bjs.ojp.gov/content/pub/pdf/p19.pdf (accessed 07/25/21). Those numbers dropped somewhat by 2019 to five times and two times the incarceration rates, respectively.

30. Steven Elías Alvarado, The Complexities of Race and Place: Childhood Neighborhood Disadvantage and Adult Incarceration for Whites, Blacks, and Latinos, SOCIUS: Sociological Research for a Dynamic World, Vol. 6: 1-18, 2020, American Sociological Association, https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/2378023120927154 (accessed 07/17/21).

31. Marc Mauer, Incarceration Rates in an International Perspective, The Sentencing Project, Jun 28, 2017.

32. Ta-Nehisi Coates is a distinguished writer in residence at NYU’s Arthur L. Carter Journalism Institute. He is the author of the bestselling books The Beautiful Struggle, We Were Eight Years in Power, and Between The World And Me, which won the National Book Award in 2015. His first novel, The Water Dancer, was released in September 2019. Ta-Nehisi is a recipient of a MacArthur Fellowship. He is also the current author of the Marvel comics The Black Panther and Captain America. https://ta-nehisicoates.com/about/ (accessed 07/17/21).

33. Ta-Nehisi Coates, The Black Family in the Age of Mass Incarceration, The Atlantic, Oct. 2015, https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2015/10/the-black-family-in-the-age-of-mass-incarceration/403246/ (accessed 11/12/21).

See also By Ta-Nehisi Coates, https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2014/06/the-case-for-reparations/361631/. “Two hundred fifty years of slavery. Ninety years of Jim Crow. Sixty years of separate but equal. Thirty-five years of racist housing policy.”

34. Jessica Jacobson, Catherine Heard, and Helen Fair, Prison, Evidence of its use and overuse from around the world, Institute for Criminal Policy Research, Birkbeck University of London, 2017, https://www.prisonstudies.org/sites/default/files/resources/downloads/global_imprisonment_web2c.pdf (accessed 07/25/21).

35. Id.

36. Id.

37. The Sentencing Project, Report to the United Nations on Racial Disparities in the U.S. Criminal Justice System, April 19, 2018, https://www.sentencingproject.org/publications/un-report-on-racial-disparities/ (accessed 07/18/21).

38. Sawyer and Wagner, Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie 2020, supra note 2.

39. Lucius Couloute, New Data Highlights Pre-Incarceration Disadvantages, Prison Policy Initiative (Mar 22, 2018), https://www.prisonpolicy.org/blog/2018/03/22/brookingsreport_2018/ (accessed Jun 18, 2021).

40. Meredith Booker, The Crippling Effect of Incarceration on Wealth, Prison Policy Initiative (Apr 26, 2016), https://www.prisonpolicy.org/blog/2016/04/26/wealth/ (accessed Jun 12, 2021).

41. Lucius Couloute & Daniel Kopf, Out of Prison & Out of Work – Unemployment Among Formerly Incarcerated People, Prison Policy Initiative (Jul 2018), https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/outofwork.html#figure2 (accessed Jun 25, 2021).

42. Sawyer and Wagner, Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie 2020, supra note 2.

43. The Sentencing Project, Americans with Criminal Records, Poverty and Opportunity Profile, Half in Ten – The Sentencing Project, https://www.sentencingproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Americans-with-Criminal-Records-Poverty-and-Opportunity-Profile.pdf (accessed Jun 9, 2021).

44. Justice News, U.S. DOJ, Office for Access to Justice, Civil Rights Division, P.Rel.No. 16-1305, updated Nov. 7, 2016, https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/justice-department-files-brief-address-automatic-suspensions-driver-s-licenses-failure-pay (accessed Jul 6, 2021). See also Fines, Fees, and Bail: Payments in the Criminal Justice System that Disproportionately Impact the Poor, Council of Economic Advisers Issue Brief (Dec 2015), https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/page/files/1215_cea_fine_fee_bail_issue_brief.pdf (accessed Jun 8, 2021) ("[Criminal Justice System f]ines and fees create large financial and human costs, all of which are disproportionately borne by the poor…. Time spent in pre-trial detention as a punishment for failure to pay debts entails large costs in the form of personal freedom and sacrificed income, as well as increasing the likelihood of job loss”).

45. Sawyer and Wagner, Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie 2020, supra note 2.

46. The Socioeconomic Impact of Pretrial Detention, Pre-publication Draft, Open Society Justice Initiative, UN Development Program (Sept 2010) https://www.justiceinitiative.org/publications/socioeconomic-impact-pret... (accessed 11/12/21).

47. Citing: Fernando Salla and Paula Rodriguez Ballesteros, Democracy, Human Rights and Prison Conditions in South America (São Paulo: 2008, Center for the Study of Violence, University of São Paulo); Penal Reform International, Prison Conditions in Africa (London: PRI and African Centre for Democracy and Human Rights, 1993); Penal Reform International, Prison Conditions in Africa (London: PRI and African Centre for Democracy and Human Rights, 1993); Advocacy Forum, Nepal, personal communication with Paul English, January 2010; Rani Dhavan Shankardass, Exploration towards accessible and equitable justice in the South Asian region; problems and paradoxes of reform (London: Penal Reform and Justice Association and Penal Reform International, 2001).

48. Jacobson, Heard, and Fair, Prison, Evidence of its use and overuse from around the world, supra note 34.

49. Legal Information Institute, Cornell Law School, https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/misdemeanor (accessed 07/03/21).

50. Alexandra Natapoff, Punishment Without Crime: How Our Massive Misdemeanor System Traps the Innocent and Makes America More Unequal, 2018. (A Publishers Weekly Best Book of 2018.) Natapoff is a Harvard Law School professor, legal scholar, and criminal justice expert.

51. Natapoff, Punishment Without Crime.

52. BJS Bulletin, State Court Processing Statistics, 2006, BJS, May 2010, NCJ 228944, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/312121363_Felony_Defendants_in_... (accessed 07/17/21).

53. Mark Motivans, Bureau of Justice Statistics, Federal Justice Statistics, 2016 – Statistical Tables, Bureau of Justice Statistics, Dec. 2020, NCJ 251772, https://bjs.ojp.gov/content/pub/pdf/fjs16st.pdf (accessed 07/17/21).

54. Alexandra Natapoff, Punishment Without Crime, supra note 50.

55. Id.

56. 511 U.S. 738, 1994.

57. See Argersinger v. Hamlin (407 U.S. 25, 1972).

58. 532 U.S. 318, 2001.

59. Sawyer and Wagner, Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie 2020, supra note 2.

60. 461 U.S. 660-661 (1983), citing Williams v. Illinois, supra, at 264 (Harlan, J., concurring); Wood v. Georgia, 450 U.S. 261, 286 -287 (1981) (White, J., dissenting).

61. Sawyer and Wagner, Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie 2020, supra note 2.

62. Michael P. Jacobson, Vincent Schiraldi, Reagan Daly & Emily Hotez, Less is More: How Reducing Probation Populations Can Improve Outcomes, Harvard Kennedy School, Malcolm Wiener Center for Social Policy, The Executive Session on Community Corrections (Aug 28, 2017), https://www.hks.harvard.edu/centers/wiener/programs/criminaljustice/research-publications/executive-sessions/executive-session-on-community-corrections/publications/less-is-more-how-reducing-probation-populations-can-improve-outcomes (accessed Jun 23, 2021) (quoting Vincent Schiraldi, Senior Research Fellow, Harvard Kennedy School Program in Criminal Justice, and former NYC Probation Commissioner).

63. Id.

64. Roopal Patel & Meghna Philip, Criminal Justice Debt: A Toolkit for Action, Brennan Center for Justice at NYU Law (2012), https://www.brennancenter.org/sites/default/files/legacy/publications/Criminal%20Justice%20Debt%20Background%20for%20web.pdf (accessed Jun 23, 2021) (“Also, several practices may violate fundamental constitutional protections”).

65. Karin D. Martin, Sandra Susan Smith & Wendy Still, Shackled to Debt: Criminal Justice Financial Obligations and the Barriers to Re-Entry They Create, New Thinking in Community Corrections, Harvard Kennedy School Program in Criminal Justice Policy and Management (Jan 2017), https://www.hks.harvard.edu/sites/default/files/centers/wiener/programs/pcj/files/shackled_to_debt.pdf (accessed Jun 14, 2021).

66. Patel and Philip, Criminal Justice Debt, supra note 64.

67. 461 U.S. 660 (1983).

68. Martin, Smith, and Still, Shackled to Debt.